For the past 18 months, my assignment with the Joint Enabling Capabilities Command enabled a different perspective on planning. On each mission, one of the products our command continually produces is an Operational Approach. The Operational approach is the culmination of operational design, and provides the commander and staff a visual of how the command visualizes the problem, along with the ways and means to achieve an endstate. While in previous assignments, the Operational Design aspect was a part of the planning, it was not stressed as an equal, or even superior product to other aspects such as Mission Analysis or Course of Action Development. I now look at Joint planning as an inverted triangle with Operational Design at the bottom, feeding the rest of the process.

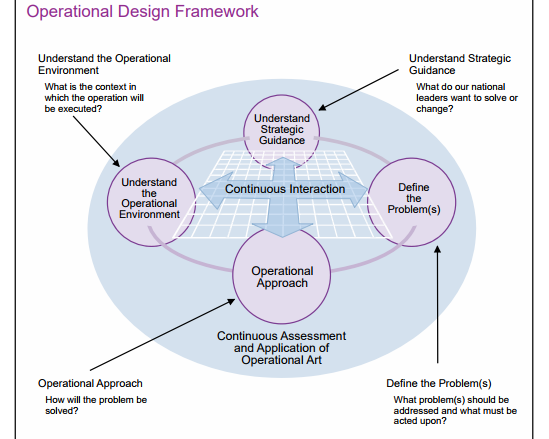

Operational design, as described in the updated Joint Publication 5-0 is "is a methodology to aid commanders and planners in organizing and understanding the Operational Environment. Operational design contains four specific components to include understanding strategic guidance, understanding the operational environment, defining the problem, and developing an operational approach.

Joint Publication 5-0.16 june 2017 Page IV-7

An Operational Approach, as defined by JP 5-0 is "a commander’s description of the broad actions the force can take to achieve an objective in support of the national objective or attain a military end state." It is within this product, that the commander and his/her staff can communicate how they envision the problem and the broad ways to solving the problem. The Operational Approach brings order from chaos.

The use of operational design to build the operational approach is the aspect of joint planning where members of the staff should be in the same place. While other parts of planning such as Mission Analysis, COA Development, and Orders Development can occur within separate cubicles, every brain is necessary at the onset. No one person within a command has a monopoly in knowledge, and everyone on the staff knows something nobody else does. All this knowledge must be brought to the table at the onset of military problem solving.

The bottom line (not up front but 4 paragraphs in) is that if the Operational Design sucks, no matter how good or thoughtful the rest of the planning process is, the final product, Operations Order, or mission will be no good, either. Indeed, planners assume the greatest risk to both the mission and to the force when they fail to consider the aspects of operational design. No matter how well conceived the mission statement at the end of Mission Analysis, or the tasks developed in COA Development, if the staff and commander are solving the wrong problem, subsequent planning and execution are fruitless endeavors, no matter how hard or long everyone works.

While the greatest risk of failure occurs at the bottom of the inverted pyramid, it is the execution of the plan that receives the most attention. It is within the execution of a Joint Operation that the greatest amount of people are acting towards an endstate. Although Clausewitzian friction is greatest in execution, if the commander has identified the right problem to solve, friction becomes easier to overcome.

Thinking of Joint Planning as an upside-down pyramid is a way to visualize where planners assume the most risk. Everything in joint planning hinges on solving the right problem, and communicating the commander's visualization of how to solve that problem to all echelons.