“Pressure is something you feel when you don’t know what you’re doing.”

– Chuck Noll, Former Head Coach of the Pittsburgh Steelers

From June of 2022 through June of 2024, I served as the Chief of the Strategy Development Division. Among our division accomplishments was the publication of the 2022 National Military Strategy, the Unified Command Plan, multiple Chairman Risk Assessments, the Joint Risk Analysis Methodology (JRAM), and the Joint Strategic Planning System (JSPS). These were the big rocks, and certainly not the only accomplishments nor the only products the team produced. However, with these accomplishments in mind, I offer the following lessons I learned as a Division Chief on the Joint Staff.

1. We all pay taxes.

Like any headquarters, the Joint Staff is full fo duty positions not specifically authorized on a JDAL or other manning type document. Front office positions such as speechwriter, director or chairman’s actions groups (DAG/CAG) will come at the expense of actions officers from various directorates and divisions. Other temporary jobs such as cross functional teams, transitions teams, Chairman’s Crisis Management Teams (CMTs) all come at the cost of personnel. New division chiefs must understand this manning dynamic, support the filling of these positions while simultaneously communicating to deputy directors the cost. The paying of manpower taxes emphasizes the importance of setting priorities within a division and communicating those priorities up and down the chain.

Furloughs continually hang above a division chief’s head like the Sword of Damocles. The tendency is that civilians working at the division level and below will not normally be designated as essential personnel during government shutdowns (unless filling an external billet/tax such as CMT). Indeed, one quickly finds that front office’s will be fully manned during these times. Again, the onus is on Division Chiefs to communicate the risk to their portfolio during government shutdowns, and then to properly prioritize the division’s efforts.

There are creative ways to mitigate personnel shortages. Advocating for a Reservist or National Guardsman on active duty orders to work in the division is one way. Looking for civilians on their way to become an SES as part of a service executive development program is another. Division chiefs can find help in some places, but nothing is guaranteed.

2. Morale is dependent upon senior leader interest.

There is little that is more demoralizing than senior leaders not caring about or having interest in a portfolio. At times there are other more pressing priorities, and other times it can be clear that the senior leader does not understand the portfolio. Both aspects will contribute to lower morale in an office.

Division chiefs must overcome the obstacle of senior leader disinterest by serving as a champion of the team’s efforts. Scheduling time with directors, deputy directors, and vice directors must be a continual effort. Indeed, providing junior actions officers the opportunities to brief senior leaders on their efforts will not only raise their morale, but also serve to develop up and coming leaders.

3. Read the Weekly

Shared understanding is a key to success in the military, be it for tactical units or for branches, divisions, and directorates on the Joint Staff. The five paragraph Operations Order includes the status of other friendly forces as a way to help understand the bigger picture. Indeed, knowing what is happening on the left, on the right, up and down, and across echelons provides perspective for all within an organization. Weekly reports serve as situational reports (SITREP) for the Joint Staff. Division Chiefs must not only provide input, but also read higher compilation of weekly reports and share that compilation with their team.

4. Know the Rules of the Game

Filling the ranks of the Joint Staff are officers and enlisted from each service, multiple components, civilians, and contractors. It is incumbent upon Division Chiefs to learn the rules that govern individuals from these various ranks.

Each service, component, and employer have different rules regarding evaluations, awards, counseling, and reporting of attendance (timecards for example). Indeed, what the Air Force values in an evaluation report can differ from what the Army values in an OER. Further, each branch in the Army has different preferences for evaluations. Recommending a strategist (FA-59) for battalion/brigade command might not be the preferred senior rater comment as it would for an infantry officer.

More than rules, it becomes apparent that civilians and contractors often have different preferences for recognition of performance. Incentives can vary from time off and monetary awards to the presentation of civilian medals (like military commendation and achievement medals). Division chiefs must learn the rules, regulations, norms, and desires of every person in every category of service.

5. Recognize your people.

Napoleon once remarked “A soldier will fight long and hard for a bit of colored ribbon.” Recognition comes in many forms including medals, coins, certificates, and can also include verbal and written recognition of accomplishments and efforts.

With medals, generally action officers will depart the Joint Staff with a PCS award of the Defense Meritorious Service Medal (DMSM). Understanding that a 2-year tour on the Joint Staff may be the only joint tour for many, division chiefs can try to find ways to award a joint service achievement medal (JSAM) for a specific accomplishment that will not fall under their normal duties. Indeed, as any officer can recommend anyone for an award, don’t limit award recommendations to only those in your division. Should an officer support your division’s efforts (in a Cross Functional Team or Working Group for example), take the time to recommend them for a JSAM or other form of recognition.

In line with knowing the rules of the game, when it comes to contractors, sending a note to their supervisors commenting on excellent performance takes little time and costs nothing. Ditto on writing up nominations for action officer of the quarter, which both civilians and military officers qualify. Coordinate with other divisions within a deputy directorate on nominations for AO and Civilian of the Quarter (fratricide = bad), and time them to coincide with the completion of major projects.

6. Develop your people.

There is no formal professional development program on the Joint Staff. Developing individuals within a division is on the division chief to find time, space, and resources to develop officers and civilians alike. This may include engagements or attendance at various think tank events (RAND, CSIS, CNAS) or attending senior leader or congressional engagements as a +1. Fortunately there is no shortage of guest speaker and author events in the Pentagon and National Capital Region.

Developing people often means empowering them. Other professional development opportunities come naturally with the job on the joint staff. Opportunities to brief a 3-Star director, the Director of the Joint Staff, the Vice Chairman, and the Chairman do arise, and generally division chiefs should position their action officers for success with these engagements. However, put your people in front of senior leaders at the right time, when they know their portfolio enough to speak confidently and answer any questions related to their products. Indeed, the great comedian Dana Gould once remarked that “bears roam the earth thinking all humans have shit in their pants…because everyone they have been up close to has shit their pants.” When sample sizes are small, first impressions matter, don’t send an unprepared action officer into the fire.

Developing people also means creating risk to manning within a division. If you do it right, contractors and civilians will develop and likely look for promotion and other career advancement opportunities such as attendance at a War College. Contractors may look to find a place in the GS system. Furthermore, there are officers who look for developmental opportunities within the staff such as serving as a speechwriter, as a member of a CAG, or as an executive assistant to a senior leader. Develop your people and support them in their careers, even if this means your division may suffer in the near-term.

Developing people becomes more important on higher echelon staffs, as division chiefs cannot make the assumption that officers arriving are trained in the specific work of the staff. Officers at Combatant Commands and the Joint Staff for example are not always JPME-II educated. Although smart and hard working, it may take time to teach officers how to roll through the joint planning process, or to properly present a mission analysis, COA development, and COA comparison. Division chiefs must take the time and have the patience to guide their AOs and branch chiefs though these processes to set them up for success when briefing senior leaders.

When a division chief develops his or her people right, the branch chiefs and action officers become experts within their portfolios. Division chiefs should constantly ask for and listen to the opinions and advice of said experts. However, know and understand when to diverge from action officer advice, and to provide your own expert and informed opinions to senior leaders.

7. The 24-month Wrecking Ball.

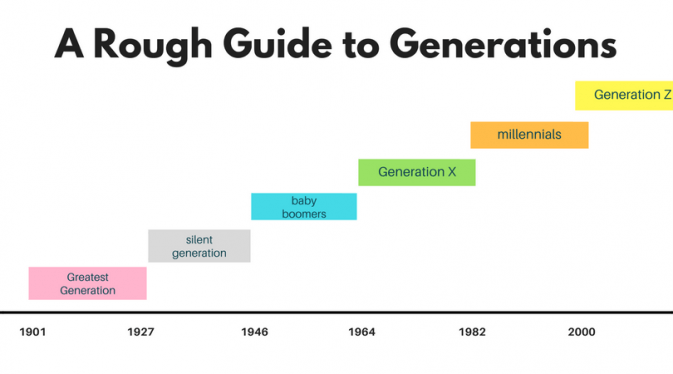

Since the passing of the 2017 NDAA, officers earn their joint credit with 24 months of joint time, 12 months shorter than when the standard was 36 months. The impact of this change often means every division will lose half their officers every summer, where in the past the personnel turnover was a more manageable third. Add in TDYs for pre-quals and pre-command training for air force officers, or pre-command course for army officers, and that 24 months gets even shorter. I have long held that reducing joint qualification time from 36 to 24 months was an unforced error in the Department, and unfortunately I don’t see the current standard changing anytime soon.

8. Manage your taskings

ETMS2, or what is commonly known as TMT (Task Management Tool) can quickly overwhelm a division or a branch if not managed properly. As a division chief I largely delegated the management of TMTs to my deputy, but kept an understanding of those taskings that mattered more than others. For example, opportunities to review and comment on documents within the Joint Strategic Planning System (JSPS) tended to rise higher in importance than others. I further provided guidance to my branch chiefs to ensure to review and comment on products that represented the strategy, or other items within our division portfolio (the UCP and the CRA for example).

Another aspect of managing TMTs included the informal discussions at the AO and O6 level to ensure early awareness of any major disagreements. Immediate coordination with AOs and O6s in other JDIRs to raise awareness of potential disagreements that would rise to the GOFO level is paramount to ensure disagreements remain friendly disagreements when there are irreconcilable differences on a specific topic.

9. Educate the Force

Strategy and doctrine are similar in that if they are not read and understood, they are worthless. Over my time as a division chief I was relentless in ensuring that my AOs, branch chiefs, and I would take the time to present our products to the Joint Force. We conducted engagements within the Joint Staff, in the building to service staffs, at Combatant Commands, throughout service and joint PME, and even to interagency and international audiences. Further, I had our team develop briefings that we could send to PME institutions to ensure our work got into the curriculum. We didn’t produce strategy for the sake of producing strategy or for meeting Title-10 demands, rather we produced strategy for the Joint Force to execute. Further, the consistent engagement to educate the force helped to build and maintain relationships across the broader strategy and plans community.

10. Know your history.

History matters, and while knowledge of military history can help, knowing and understanding the history of various strategic documents in a portfolio is a key to success. Knowing why a document exists, why it has the classification it does, and why various statements, timelines, or tasks within a document are present is critical. Did the tasks come directly from the Chairman, Vice Chairman, or Director? Was there a change directed in an NDAA? Division Chiefs should keep in contact with their predecessors to help provide context for senior leaders as to why documents are the way they are when it comes time to review and rewrite them.